Our website is made possible by displaying online advertisements to our visitors.

Please consider supporting us by disabling your ad blocker.

Superfluidity

| Condensed matter physics |

|---|

|

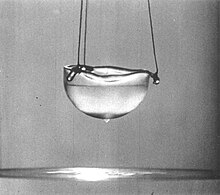

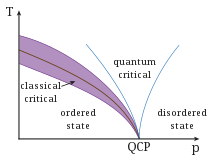

Superfluidity is the characteristic property of a fluid with zero viscosity which therefore flows without any loss of kinetic energy. When stirred, a superfluid forms vortices that continue to rotate indefinitely. Superfluidity occurs in two isotopes of helium (helium-3 and helium-4) when they are liquefied by cooling to cryogenic temperatures. It is also a property of various other exotic states of matter theorized to exist in astrophysics, high-energy physics, and theories of quantum gravity.[1] The theory of superfluidity was developed by Soviet theoretical physicists Lev Landau and Isaak Khalatnikov.

Superfluidity often co-occurs with Bose–Einstein condensation, but neither phenomenon is directly related to the other; not all Bose–Einstein condensates can be regarded as superfluids, and not all superfluids are Bose–Einstein condensates.[citation needed] Superfluids have some potential practical uses, such as dissolving substances in a quantum solvent.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physics 1996 – Advanced Information". www.nobelprize.org. Retrieved 2017-02-10.

Previous Page Next Page