Our website is made possible by displaying online advertisements to our visitors.

Please consider supporting us by disabling your ad blocker.

Science of reading

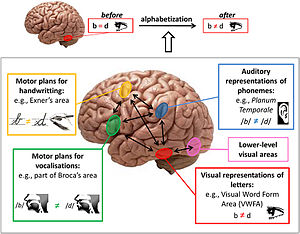

The science of reading (SOR) is the discipline that studies reading.[4] Foundational skills such as phonics, decoding, and phonemic awareness are considered to be important parts of the science of reading, but they are not the only ingredients. SOR includes any research and evidence about how humans learn to read, and how reading should be taught. This includes areas such as oral reading fluency, vocabulary, morphology, reading comprehension, text, spelling and pronunciation, thinking strategies, oral language proficiency, working memory training, and written language performance (e.g., cohesion, sentence combining/reducing).[5]

In addition, some educators feel that SOR should include digital literacy; background knowledge; content-rich instruction; infrastructural pillars (curriculum, reimagined teacher preparation, and leadership); adaptive teaching (recognizing the student's individual, culture, and linguistic strengths); bi-literacy development; equity, social justice and supporting underserved populations (e.g., students from low-income backgrounds).[4]

Some researchers suggest there is a need for more studies on the relationship between theory and practice. They say "We know more about the science of reading than about the science of teaching based on the science of reading", and "there are many layers between basic science findings and teacher implementation that must be traversed".[4]

In cognitive science, there is likely no area that has been more successful than the study of reading. Yet, in many countries reading levels are considered low. In the United States, the 2019 Nation's Report Card reported that 34% of grade-four public school students performed at or above the NAEP proficient level (solid academic performance) and 65% performed at or above the basic level (partial mastery of the proficient level skills).[6] As reported in the PIRLS study, the United States ranked 15th out of 50 countries, for reading comprehension levels of fourth-graders.[7] In addition, according to the 2011–2018 PIAAC study, out of 39 countries the United States ranked 19th for literacy levels of adults 16 to 65; and 16.9% of adults in the United States read at or below level one (out of five levels).[8][9]

Many researchers are concerned that low reading levels are due to how reading is taught. They point to three areas:

- Contemporary reading science has had very little impact on educational practice—mainly because of a "two-cultures problem separating science and education".

- Current teaching practice rests on outdated assumptions that make learning to read harder than it needs to be.

- Connecting evidence-based practice to educational practice would be beneficial, but is extremely difficult to achieve due to a lack of adequate training in the science of reading among many teachers.[10][11][12][13]

- ^ "Human language may have evolved to help our ancestors make tools, Science Magazine". January 13, 2015.

- ^ Stanislas Dehaene (2009). Reading in the brain. Penguin books. p. 63. ISBN 978-0-670-02110-9.

- ^ Mark Seidenberg (2017). Language at the speed of light. Basic Books. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-465-08065-6.

- ^ a b c "Making Sense of the Science of Reading". literacyworldwide.org.

- ^ "What Is the Science of Reading, Timothy Shanahan, Reading Rockets". 2019-05-29.

- ^ "NAEP 2019 grade 4 reading report" (PDF).

- ^ cite web|url=https://pirls2016.org/wp-content/uploads/structure/PIRLS/3.-achievement-in-purposes-and-comprehension-processes/3_1_achievement-in-reading-purposes.pdf%7Ctitle=PIRLSdate=2016

- ^ Skills Matter: Additional Results from the Survey of Adult Skills (PDF). OECD Skills Studies. OECD Skills Studies. 2019. p. 44. doi:10.1787/1f029d8f-en. ISBN 978-92-64-60466-7. S2CID 243226424.

- ^ Skills Matter: Additional Results from the Survey of Adult Skills (PDF). OECD Skills Studies. OECD Skills Studies. 2019. p. 44. doi:10.1787/1f029d8f-en. ISBN 978-92-64-60466-7. S2CID 243226424.

- ^ Seidenberg, M. S. (2013-08-26). "The Science of Reading and Its Educational Implications". Language Learning and Development. 9 (4): 331–360. doi:10.1080/15475441.2013.812017. PMC 4020782. PMID 24839408.

- ^ Stanislas Dehaene (2010). Reading in the brain. Penguin Books. pp. 218–234. ISBN 978-0-14-311805-3.

- ^ Kamil, Michael L.; Pearson, P. David; Moje, Elizabeth Birr; Afflerbach, Peter (2011). Handbook of Reading Research, Volume IV. Routledge. p. 630. ISBN 978-0-8058-5342-1.

- ^ Louisa C. Moats. "Teaching Reading Is Rocket Science, American Federation of Teachers, Washington, DC, USA, 2020" (PDF). p. 5.

Previous Page Next Page